Angel In Flames

Angel In Flames

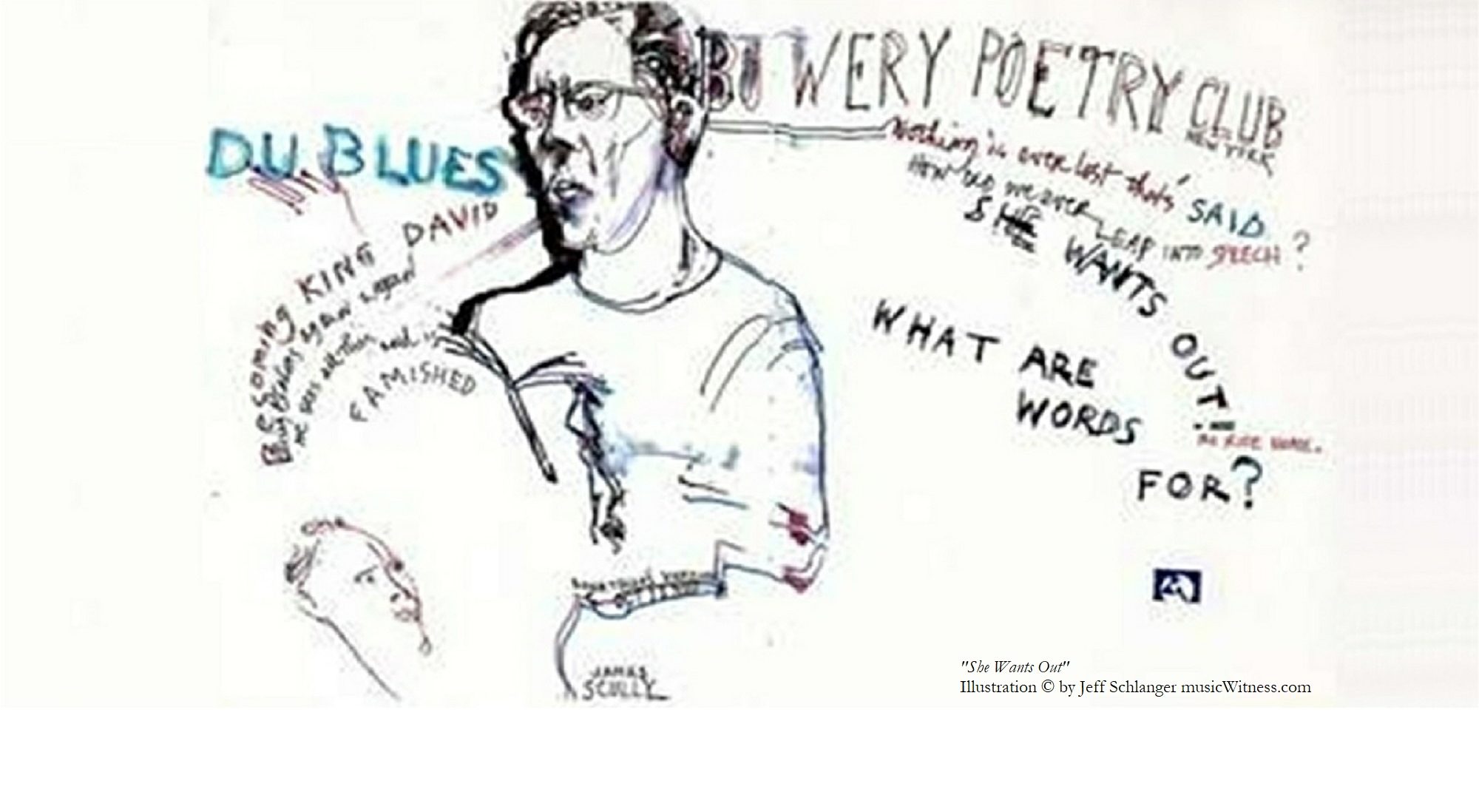

by James Scully

ISBN 978-0-9564175-8-9

£8.95

Reviewed by Alan Dent

Mistress Quickly’s Bed (UK)

James Scully has been publishing since 1967 and has ten volumes of poetry to his name, among other publications. He’s a mainly small press American poet previously unpublished in Britain. I’d be surprised if many poetry readers in this country know his work. I didn’t and he’s the kind of poet I like. Beyond the matter of taste is the question whether his poetry stands up to scrutiny. The book is divided into two sections: after 2004 and before. There is no strong sense that his work has changed greatly or improved markedly over the decades, though there is clearly greater maturity in the later pieces, evident principally in tone. There’s a piece called Poetic Diction from the earlier work:

Certain words are not fit

for poetry .

Boss, for instance

Our better verse

you may observe

has no boss in it.

The fifth line carries the weight: the tone of expertise, the kind of thing you expect to hear from the lectern. It is expertly placed to disrupt what might start to sound like polemic and to divert the reader’s attention to a contrary voice. The poem continues in this vein till it concludes that This is why no-one/ minds /poetry any more. I’ve picked out this poem because it encapsulates what the collection is concerned with: a civilization in denial, needing to change but lacking the courage to change, clinging to irrelevant values and inevitably dragging culture down with it as it commits slow suicide. Scully’s writing, from the beginning, is suffused with this sense of cutting against the grain. The entire collection asks the question: what can poetry do in such a world ? Where is the space it can survive ? What is the form it needs to take to have some purchase on present-day reality ? Samuel Beckett posed a kindred question when he remarked: To find a form to accommodate the mess, that is the task of the artist now. Scully’s achievement is to have found a form. It consists in using simple, straightforward language, creating an architecture which is easy to follow, allowing metaphors and images to emerge rather than imposing them, and working through complex ideas and experiences in a down-beat way. I’m reminded of Einstein’s chirpy remark when asked to put Relativity in simple terms: You sit on a hot stove for a minute, it seems like an hour; you sit next to a pretty girl for an hour it seems like a minute. That’s Relativity.Behind the joke is a serious point: what happens depends on where in the universe you observe it from. Scully is a bit like this. He has very serious and complicated things to say, but he doesn’t want to write like a clever-dick. He doesn’t want to hide behind difficulty or show off his superior learning or sensibility. On the contrary, what all his poetry is driving at is that just as we have created economic abundance but don’t know how to share it, so we have created mass literacy but don’t know what to do with it. Writers always have an implied reader in mind. Publishers know that most novels are bought by women and many of them live in the Home Counties, so the volumes written for go-getting women in Reigate pile up in Waterstones. Scully’s implied reader is the educated, democratic citizen, the kind of figure Whitman would have recognised and Scully wants this citizen to assume his and her proper place in the world. This is not to suggest he’s toying with the fantasy of turning the masses into intellectuals; rather he’s putting faith in the power of culture to educate the sensibility. Shortly before he died, Jose Saramago commented that it was futile to try to get the majority to read seriously. Such reading has been and will remain the province of the few. I take him to mean precisely that you can’t make the masses into intellectuals; but that doesn’t imply a culture of quiz shows and celebrities’ backsides. Scully’s poetry is aware of being caught up in a culture war. There is no space in which poetry is allowed to live untroubled by the struggle over property and power. How then to put pen to paper ? Scully’s poems clear a little area of ground for themselves, chop away the brambles:

Up in a clearing of the wood, beyond

the wavering incline behind our house

wild among scrub and poison ivy –

we find the high bush variety.

He’s writing about blueberries but the poem soon begins to question the nature of modern existence; we aren’t innocent about nature anymore; we know how the world will end and when; we have conned essential mysteries, but knowing our place in the universe doesn’t help us get on with one another. I think it’s important to acknowledge just how far our consciousness has been transformed by modern cosmology. Until quite recently, say at least before the publication of The Origin of Species, virtually every poet was writing from the confident sense of humanity’s special place in the order of things and a faith that we are fulfilling a destiny laid down by benign forces. There are still plenty of fanatics and deniers of one persuasion or another who refuse the evidence, but everyone who addresses the science seriously knows we have a brief tenancy of a doomed planet. The hubris that comes from believing the universe was made for humanity is impossible in the light of this. But much more. No significance is ultimate. There is no eternal redemption. We can’t justify today’s cruelty by reference to some putative existence beyond existence. The world wasn’t made for humanity but humanity for the world. Of course, it’s still possible to wriggle free and believe in an afterlife and eternal existence. No science can dislodge faith. But faith or not the earth has a finite existence; the sun will become a red giant and burn our planet like a ball of paper on a bonfire. No more people with immortal souls will be born long before that. We’ll be lucky if we’re around another two hundred thousand years. Scully’s poetry is full of this kind of disillusioned sensibility:

what is human-

a species of matter

cutting the water in long canoes

stroking the spume of passion, beauty, blood

terrified, terrifying

Scully understands how our cosmology keys into our history: if you believe the universe is ruled by a single, omnipotent deity (just as if you believe History is process without a subject) you tend to believe society should be governed in the same way; if the will of the deity cannot be defied, why should the will of the ruler ?; if earthly life is mere preparation for the real thing, what does it matter if millions die in wars ?; if killing the infidel brings eternal reward why not genocide ? This poetry is full of the necessity of a more modest and straitened view of ourselves. It is the work of a rare sensibility. Scully knows that our confusion about our human status makes us monsters to ourselves, full of hubris, believing we know where we’re going as we grope in the dark along a road without signs or landmarks willing to injure and kill others in pursuit of our demented sense of importance and justification. This collection is a plea for humility; species humility as well as personal. It is a plea expressed in beautiful, expert poetry. Let’s hope there will be a posterity which will grant Scully the praise he deserves.