A struggle for breath

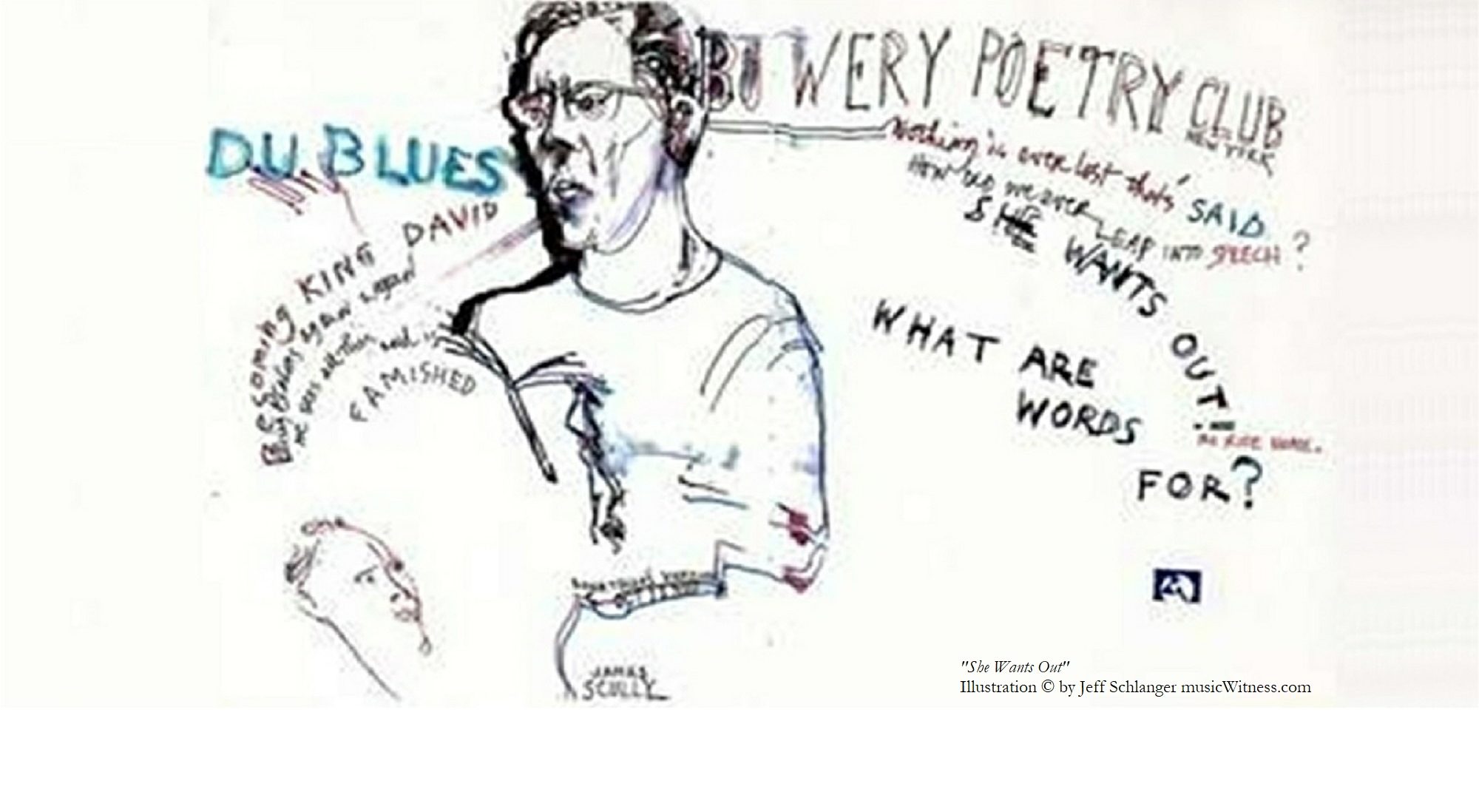

Monday 10 October 2011 by Andy Croft

In 1973 the US poet Jim Scully won a prestigious Guggenheim Fellowship to travel abroad for a year. Excited by the achievements of the Allende  government in Chile, he decided to move his young family to Santiago.

government in Chile, he decided to move his young family to Santiago.

They were en route in Mexico when the army overthrew the government and murdered Allende in the Chilean capital.

“We went on to Chile anyway, figuring the military would assume I was a US agent, which they did,” Scully recalls.

“Access to the Pudahuel airport was restricted to soldiers and Dina, the intelligence police, mostly guys in business suits carrying automatic weapons. They didn’t even check our bags.

“We were North Americans, our kids were blonde, we were arriving on the heels of the ‘golpe’ – who else could we be but who we had to be?”

Although Jim and his wife Arlene had been involved in the anti-war movement in New Jersey in the early 1960s, living in Chile in the aftermath of the US-backed Pinochet coup was a brutal introduction to political realities.

“Imagine witnessing a woman from the Israeli consulate negotiating a shipment of Uzis with a colonel of the carabineros at a party with one of the Chicago Boys present,” he says.

One of their neighbours was Isabel Letelier, then living under house arrest. Her husband, who had been Allende’s Defence Minister, was later murdered by a car bomb in Washington.

For a while, the Scullys’ Santiago apartment was used as a safe house by the MIR (Movimiento de Izquierda Revolucionaria) guerillas.

“They’d borrowed Avenue Of The Americas, a book of my poems, returning it with the verdict: ‘a little bit hippy, a little Trotskyite, but very definitely left.’ And smiled. They had a certain innocence, as did we. No reality is contained by its stereotype.”

Scully returned to the US with his collection Santiago Poems and Sandy Taylor created the now legendary Curbstone Press in order to publish chilling lines like: “Behind a TV screen/as in a shadow play/the general gavels his fist./His captive audience/is 10 million souls…When he opens his mouth/all Santiago/contracts to a shrunken head.”

The Scullys joined the Progressive Labour Party – “lots of street action for five years with some wonderful people, mostly Puerto Rican” – but later Scully and Taylor were arrested on weapons charges related to anti-KKK activity.

In the late 1970s they published Art On The Line, a series of Curbstone booklets by Roque Dalton, Cesar Vallejo, George Grosz, John Heartfield and Wieland Herzfelde.

It was a brave attempt to inform and raise a few caveats with mainstream US poetry. But it wasn’t, of course, listening.

“The mainstream does not critically engage with work outside its realm. How could it? It can’t critically engage itself,” Scully declares.

“The poetic field is no less a political construct than an aesthetic one. When we speak of mainstream poetry we’re talking basically about academic poetry, poetry in its institutional aspect, which is the basis for jobs, careers, publications and poetic norms. It’s where the continuity of money and recognition is maintained.

“There’s a lot of cute, too-clever-by-half poetry without an ounce of gravity, and of course no resonance. It seems we lack even the language with which to speak social or civic reality.”

Finding that his poetry was unpublishable in US magazines, Scully gave up writing poetry altogether for many years. He began to write critical essays, Line Break: Poetry As Social Practice being one of his better known.

But when the Bush regime broke out its ready-made “war on terror” immediately after the events of September 11 2001 he began writing poetry again.

“By that time the postmodernist thing was incapable of landing hard enough to say anything about anything,” he says.

“Worse, it had extended the tenure of social silence, leaving an opening only for identity politics and the academic discipline called post-colonialism – this with nearly a 1,000 US military bases, some the size of small cities, installed across the world.”

It is fair to say that Scully is not a fan of Bush’s successor in the White House. “Obama’s job, for which he was groomed, and which he’s accomplishing with stunning success, is to do for the US what Yeltsin did for Russia – accelerate the massive transfer of public wealth into private hands.

“I never anticipated the breakdown would be so vast, thorough and bald-faced. The enclosure laws of Tudor times and later were a primitive version of this sort of thing.”

In the last decade Scully has been writing furiously as though to make up for lost time. He has recently published three collections of poetry, a travel book about the break-up of Yugoslavia and a new translation with Bob Bagg of Sophocles’ plays.

And Smokestack have just brought out Angel In Flames, a collection of the best of his poems and translations from the last 40 years.

The collection is an extraordinary achievement by any standards, an eloquent and stubborn witness to the victory march of imperialism – “so Agamemnon lords it still, /Menelaos struts and struts, /they can’t stop / lording and strutting… and when the gods are gone/ into the long, drunken night – /gods of the globe /drunk with blood, drunk with money,/with hatred of life/we will go after them / into the same night.”

Scully points out that the ancient Greeks called “apolitical” citizens – those who care only for their own personal interests – “idiotai,”the opposite of politai, citizens in the “true” sense.

“For the Greek tragedians, the primary point of collective reference was society, not the individual,” Scully says. “They took everything on and in front of everyone. Full-bodied, adult stuff. Not crimped by the servility that comes of habitual evasiveness.”

Among the classical poets Scully most admires is the sixth-century BCE soldier-poet Archilochos, who is supposed to have said that “the fox knows many things; the hedgehog one big thing.”

For Scully, the one big thing is the belief that “poetry is a struggle for breath.” He says: “We write poems not because we want to but because we have to. I feel the necessity of speaking to where the social silence is. I’d prefer to be writing other things, but conscience gets me and won’t let go.”

James Scully, Angel in Flames: Selected Poems and Translations 1967-2011 is available for £8.95 (postage free) from Smokestack Books, PO Box 408, Middlesbrough TS5 6WA; info@smokestack-books.co.uk; or visit Smokestack Books.

If you have enjoyed this article then please consider donating to the Morning Star’s Fighting Fund to ensure we can keep publishing your paper.